Brazil in the Belt and Road Initiative and Digital Silk Road

A brief overview of the integration

versão portuguesa disponível

Fourth article of this project Research for this project was supported by the Graduate Startup Interns Program and the Virtual Immersions and Experiential Work Program (both at Georgetown University).

Introduction

A chief reality among the various relations in the emerging market nations today is the presence of Brazil as a major player in international affairs. This is evident in a few ways. First, Brazil’s size gives its stature greater weight in diplomatic conversations. Second, Brazil is a leading member of the impactful BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) coalition at a time when the bloc is reflecting the empowerment of more non-Western actors and perspectives. Third, and in some ways most importantly, Brazil is the leading state among nations of a given shared colonial identity: the Portuguese-speaking countries. These countries are significant to consider in modern international affairs given their geographically strategic locations as well as their representation of many concerns and priorities of smaller and developing countries at the present time. [1] This notably extends to the promise and influence of expanding capabilities and reliance on information communication technologies (ICTs) and take advantage of the latest wave of global innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) [2].

Given this backdrop, it makes sense that great powers would be actively engaged in the policy calculations of an influential state like Brazil. Here, China appears to be a nation currently devoted to spreading its soft power around the world while identifying new markets for its newest products, as the case study of its activities in Brazil clearly highlight. Beijing shows a vested interest in pursuing more integrated affairs with Brasilia on a number of fronts. This article will focus specifically on how ICT is playing a role in this diplomacy – from its avenues towards successful harmony between the two nations to the challenges that have and continue to persist on a bilateral scale – that occur outside of traditional multilateralism. From this we see how Brazil has grown closer to Chinese policies and technological markets in recent years, as well as how broader Chinese foreign policy mechanisms like the Digital Silk Road (DSR) [3] can carry the relationship further. That said, differences in human rights remain key impediments to further cooperation [4], making the relationship as mediated through ICT one of many key arbiters of China’s true global reach in the 21st century.

Avenues For Cooperation

DSR works to establish Chinese product standards internationally (and especially in Latin America) and incentivize countries to drive a wedge between Washington and Beijing [5], creating complex policy calculus in Brasilia. The Sino-Brazilian relationship was forged through agreements like the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on “Information and Communications Cooperation between the Ministry of Communications and the National Telecommunications Agency in Brazil and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology in China.” [6] PRC support comes as Brazil is becoming a leader in e-government and digitization policy [7]. Brazil has also received previous ICT development assistance for improving empirical decision-making in critical sectors of land management including the administration of protected areas [8].

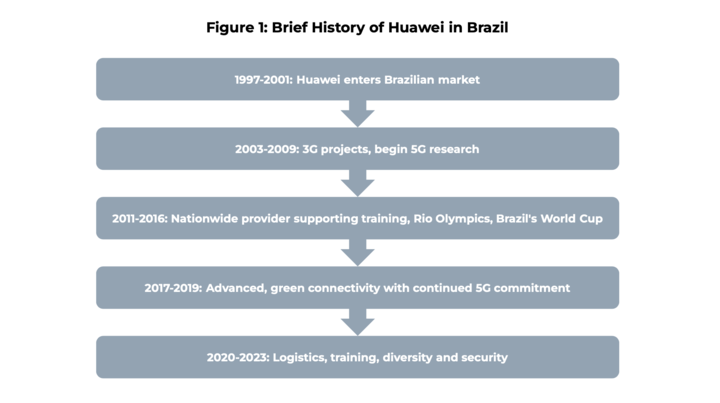

An illuminating example of Sino-Brazilian relationship considerations in this area is in Brazil’s stance towards Chinese ICT infrastructure. Companies like China Telecom have a large presence and cloud offerings in the Brazilian market [9], which may indicate that Brazil is trying to play the US and China against each other in foundational components like semiconductor manufacturing [10]. PRC champion firms like Huawei are an attractive option for Brazil due to previous records supplying 4G and 5G coverage, meeting a weakness in Brazil’s ICT economy noted in poor high-speed data coverage related to its regional peers [11]. Figure 1 below highlights Huawei’s quarter century in Brazil through anecdotal evidence of sustained investment [12].

Consequences of Integration

As a consequence, analysts like Adriana Abedenur identify “ripple effect” from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) where Huawei contributes to Brazilian development and in turn brings closer Brazilian ties to Beijing. The “ripple effect” is seen when examining Brazil’s strong ICT manufacturing economy [13]. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula”) expressed approval for Huawei and has presided PRC aid to establish satellite technology over the Brazilian Amazon, extending a long history of cooperative bilateral relationship on satellites [14]. This diplomacy appears to continue under the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS) program [15] and newly secured trade deals/MOUs reached in 2024 giving Brazil enhanced low-earth orbit capabilities to reduce dependence on singular providers like Starlink [16]. Brazil’s cooperation is importantly multi-partisan, as former President Jair Bolsonaro also supported Huawei by allowing the company to build Brazilian ICT infrastructure [17].

However, this picture challenges Brazil’s “unaligned” global status and posture of “politica externa ativa e altiva” (active and proud foreign policy), as China invests in semiconductor manufacturing with research and development (R&D) institutions like the Centro de Excelência em Eletrónica Avançada (CEITEC) and 11 concurrent production centers. This puts Brasilia in a predicament sandwiched between the US and China, complicating Brazil’s diplomatic interests in other places like resolving Ukraine-Russia conflicts [18]. That said, Chinese influence remains strong in Brazil even with little evidence of formal disinformation driven by PRC interests. The most malign campaigns in this area are generally in Chinese diaspora communities and Beijing’s relationships with local media outlets [19].

A salient divergence point in modern Sino-Brazilian affairs is labor policy, with high implications for the global ICT sector thanks to the introduction of BYD as a foreign manufacturer in Brazil. Initially slated to expand the PRC’s internationally-leading electric vehicles (EV) industry, BYD activities in Brazil instead invited negative scrutiny that may erode some goodwill for China in the fellow BRICS member nation. Brazilian authorities investigated and concluded that BYD abused and illegally employed PRC nationals sent to Brazil to provide cheap labor, which brought the firm’s general compliance in the country into question. This underscores Brazil’s strong labor movement and enforcement, a marker which may not weaken as Chinese firms attempt to penetrate one of the world’s largest EV markets [20].

Thoughts About Future Relations

The vicissitudes of political power in a large country like Brazil present a meaningful series of case studies into the impact on partisanship on ICT-related diplomacy. In the case of Brazil, swings in presidencies from right wing to left wing [21] leave perhaps its firmest mark in foreign policy in Brasilia’s relations with great powers. Among these fellow large and influential states, China is probably the most important to consider today because of its intent to pursue an active diplomacy designed to spread its technological prowess around the world. In Brazil, China has adapted its model for ICT development, collaboration, and cooperation with a modicum of success given its recent history of providing a firm foundation for notable Chinese tech conglomerates like Huawei to grow and solidify in the country [22]. China is continuing to elaborate on such a strategy of introducing advanced technological capabilities to emerging market states like Brazil on a scope that may be difficult for other state actors to match and duplicate.

Yet Brazil also appears to be heading in a direction towards greater policy and economic independence, asserting its perceived strength as a growing influential voice in global affairs. Such a standpoint may prove difficult for China, as its model in Brazil thus far appears predicated more on Sino-dominated terms in policy and technology implementation, spread, and market penetration. In this way, the more recent pushback against Chinese business practices in the name of human rights protections further highlight a cleavage in governance priorities between China and Brazil [23]. Thus, a focus on the dynamics of Sino-Brazilian affairs, combined with further analysis on Brazil’s ICT and AI adoption tactics, policies, and record, provide useful clues for both China’s future calculations in its international development strategy and the ongoing nature of policy arrangements that leverage ICT for sustainable growth in emerging market states.

References

- William J. Vogt, “China and Lusophonia: A Compatible Alliance Network?”, China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 3, no. 4 (2017): 551-573.

- William J. Vogt, “Foundations of the Chinese Internet”, Kendall Hunt, 2023.

- Jorge Malena, “The Extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and Potential Risks the DSR’s Origins and Its Initial Development.”, ResearchGate (January 2021). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jorge-Malena/publication/348786829_The_Extension_of_the_Digital_Silk_Road_to_Latin_America_Advantages_and_Potential_Risks_The_DSR's_Origins_and_Its_Initial_Development/links/60104f32299bf1b33e286848/The-Extension-of-the-Digital-Silk-Road-to-Latin-America-Advantages-and-Potential-Risks-The-DSRs-Origins-and-Its-Initial-Development.pdf

- Mandy Zuo and He Huifeng, “China EV giant BYD hits the skids in Brazil as ‘slavery-like’ claims run over labour force.”, South China Morning Post (9 January 2025). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3293923/china-ev-giant-byd-hits-skids-brazil-slavery-claims-run-over-labour-force?module=top_story&pgtype=homepage

- Jorge Malena, “The Extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and Potential Risks the DSR’s Origins and Its Initial Development.”, ResearchGate (January 2021). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jorge-Malena/publication/348786829_The_Extension_of_the_Digital_Silk_Road_to_Latin_America_Advantages_and_Potential_Risks_The_DSR's_Origins_and_Its_Initial_Development/links/60104f32299bf1b33e286848/The-Extension-of-the-Digital-Silk-Road-to-Latin-America-Advantages-and-Potential-Risks-The-DSRs-Origins-and-Its-Initial-Development.pdf

- Carolina Souza and Iago Sousa, “Brazil-China Cooperation.”, Observa China (23 December 2023). Available at: www.observachina.org/en/articles/cooperacao-brasil-china.

- Linda Bower, “Brazil as a leader in digital transformation.”, ICEGOV ’23: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (Sept. 2023): 80–85. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3614321.3614332.

- USAID, “Environmental Partnerships in Brazil”, 2020. Available at: 2017-2020.usaid.gov/brazil/our-work/environmental-partnerships.

- Ron Supan, “China Telecom Expands to Brazil With First Cloud Service Launch.”, China Telecom Americas (17 Jan. 2024). Available at: www.ctamericas.com/press/china-telecom-launches-its-first-cloud-offering-in-brazil.

- Ryan C. Berg and Carlos Baena, “The Great Balancing Act: Lula in China and the Future of U.S.-Brazil Relations.”, Center for Strategic and International Studies (25 Sept. 2024). Available at: www.csis.org/analysis/great-balancing-act-lula-china-and-future-us-brazil-relations.

- Centro Nacional de Inteligencia Artificial (Chile), “Indice Latinoamericano de Inteligencia Artificial.” (2024). Available at: https://indicelatam.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ILIA_2024_2.pdf

- “Digital Brazil: Huawei and the Pride to Build the Present and the Future.”, Huawei (2 October 2023). Available at: https://issuu.com/convergenciadigital/docs/huaweibrasil25anos_english

- Adriana Abedenur, “Navigating the Ripple Effects: Brazil-China Relations in Light of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).” Instituto Igarapé (17 Oct. 2019). Available at: https://igarape.org.br/en/navigating-the-ripple-effects-brazil-china-relations-in-light-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative-bri.

- Ana Soliz De Stange, “China and Brazil’s Cooperation in the Satellite Sector: Implications for the United States”, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (14 June 2023). Available at: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3428204/china-and-brazils-cooperation-in-the-satellite-sector-implications-for-the-unit/

- Aline Chianca Dantas, "Cooperação Sul-Sul entre Brasil e China: uma análise das iniciativas em ciência, tecnologia e inovação.", IPEA (2023). Available at: https://www.ipea.gov.br/revistas/index.php/rtm/article/view/435

- Igor Patrick and Mark Magnier, “Xi Jinping meets with Brazilian president Lula, signing 37 trade and development deals.”, South China Morning Post (20 November 2024). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3287438/xi-jinping-meets-brazilian-president-lula-signing-over-30-agreements?module=top_story&pgtype=homepage

- Neil Law, “China’s Digital Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean.”, Air University (AU) (5 Oct. 2023). Available at: www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3540684/chinas-digital-influence-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-implications-for-th.

- Ryan C. Berg and Carlos Baena, “The Great Balancing Act: Lula in China and the Future of U.S.-Brazil Relations.”, Center for Strategic and International Studies (25 Sept. 2024). Available at: www.csis.org/analysis/great-balancing-act-lula-china-and-future-us-brazil-relations.

- “Brazil.”, Freedom House (2022). Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/beijings-global-media-influence/2022.

- Mandy Zuo and He Huifeng, “China EV giant BYD hits the skids in Brazil as ‘slavery-like’ claims run over labour force.”, South China Morning Post (9 January 2025). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3293923/china-ev-giant-byd-hits-skids-brazil-slavery-claims-run-over-labour-force?module=top_story&pgtype=homepage

- Igor Patrick and Mark Magnier, “Xi Jinping meets with Brazilian president Lula, signing 37 trade and development deals.”, South China Morning Post (20 November 2024). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3287438/xi-jinping-meets-brazilian-president-lula-signing-over-30-agreements?module=top_story&pgtype=homepage

- “Digital Brazil: Huawei and the Pride to Build the Present and the Future.”, Huawei (2 October 2023). Available at: https://issuu.com/convergenciadigital/docs/huaweibrasil25anos_english

- Mandy Zuo and He Huifeng, “China EV giant BYD hits the skids in Brazil as ‘slavery-like’ claims run over labour force.”, South China Morning Post (9 January 2025). Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3293923/china-ev-giant-byd-hits-skids-brazil-slavery-claims-run-over-labour-force?module=top_story&pgtype=homepage

This article is part of the project Chinese Technological Investment in PortugueseSpeaking Countries. Learn more about this and other projects here.

The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the institutional position of Observa China 观中国 and are the sole responsibility of the author.

OBSERVA CHINA 观中国 BULLETIN

Subscribe to the bi-weekly newsletter to know everything about those who think and analyze today's China.

© 2026 Observa China 观中国. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy & Terms and Conditions of Use.