Artificial Intelligence

The Next Phase of Sino-Lusophone Relations

versão portuguesa disponível

Second article of this project Research for this project was supported by the Graduate Startup Interns Program and the Virtual Immersions and Experiential Work Program (both at Georgetown University).

Introduction

The advent of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) technologies is a defining characteristic of modern economic, social, and political affairs. The earth-shaking effects of such a trend include advancing individual societies towards a “singularity” that bakes in norms, cultures, and processes that could direct the path of humanity in the foreseeable future. [1] Such a reality comes into greater focus when looking at developing societies like those in the Portuguese-speaking states.

AI’s rise in the present moment reflects a new truism wherein technological innovation – and the cultural implications that arise because of it – may have a new, non-Western source of inspiration. Here, the emergence of China as a world power comes as Beijing continues to innovate advanced information communication technologies (ICTs), notably investing in breakthrough AI platforms. The design, implementation, and prompting mechanisms behind this likely represent the first time a wave of technological innovation has developed independently of initial Western inputs; this importantly extends to concepts uniting Chinese and Western AI development such as retrieval augmented generation (RAG) which is now seen to hold “Chinese characteristics.” [2]

This article thus highlights how Chinese global influence in areas like AI presents an attractive model to non-Western, post-colonial nations. Politically, this allows such emerging market states to explore viable development options outside of widely-known traditional Western financing models [3]. In this way, the majority of the Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) states are a notable case study worth examining for two major reasons. First, they have adopted a multilateral and institutional approach to tech and AI diplomacy that streamlines feasible policymaking. Second, these states’ interests dovetail well with Beijing’s contemporary strategic direction, underscoring potentially powerful international relations between China and these countries. As a result, the Portuguese-speaking countries represent a leading model for analysis to continue to observe as AI – and Chinese AI in particular – continue to develop.

AI Strategies

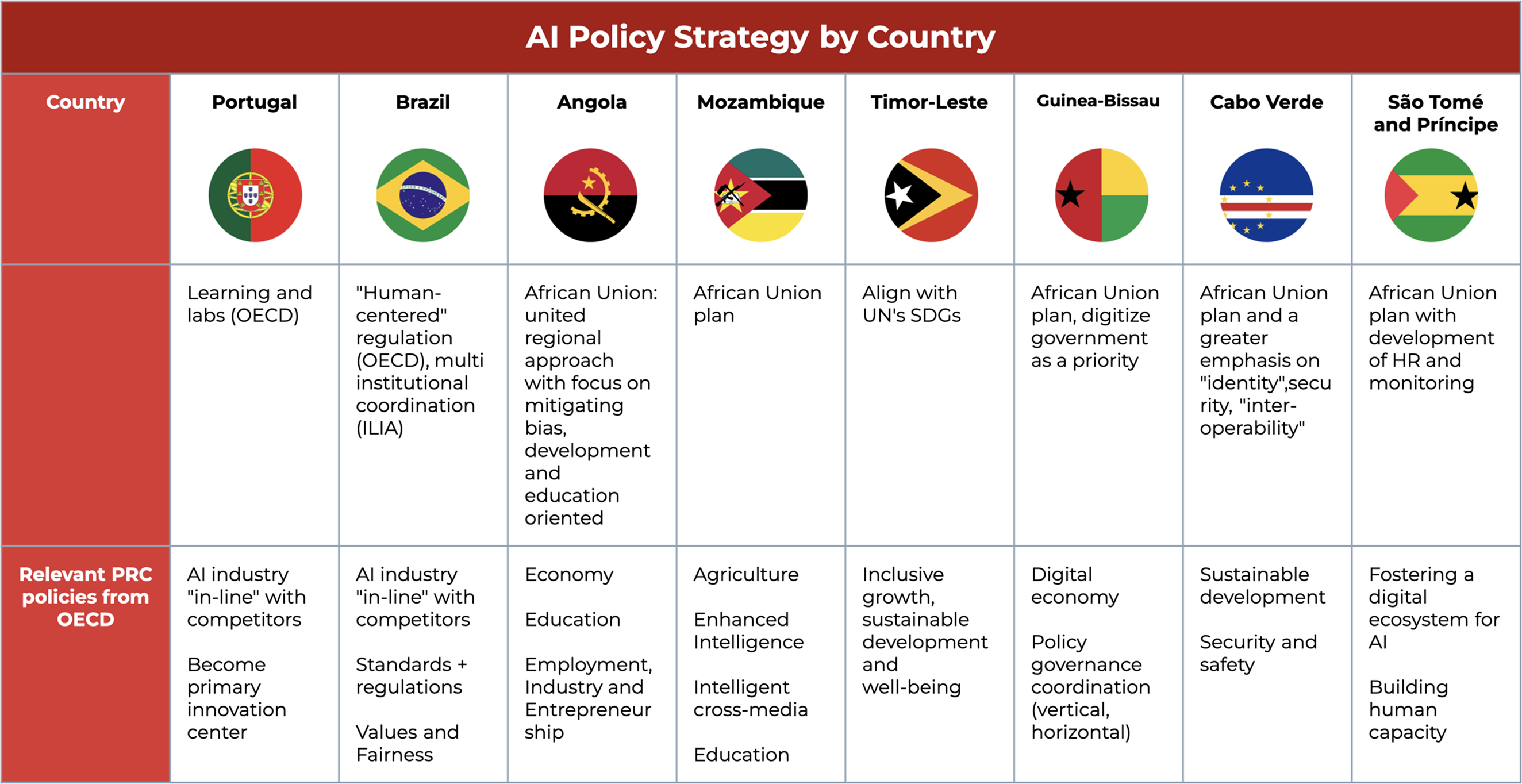

Figure 1: AI Policy Strategy by Country (2024)

Sources: African Union [4], Tatoli [5], GovInsider [6], United Nations University [7] [8],OECD [9]

Sources: African Union [4], Tatoli [5], GovInsider [6], United Nations University [7] [8],OECD [9]

Unifying Trends Across Lusophonia

AI is the seminal topic today, and China is a leader in driving advancements in the industry. This has significant impacts for Lusophone countries incentivized to carry out bespoke strategies to leverage the technology to support growth goals. Figure 1 outlines how each Lusophone state addresses regulation and development in the early years of AI. This roadmap could guide continued foreign direct investment (FDI) trends in AI in these countries for years to come. Several Lusophone states are already significant recipients of AI development aid, with Angola, Mozambique, and Timor-Leste in particular benefitting from investment in health, agriculture, governance, and improving macroeconomies. [10]

Consequently, policymaking and standards setting efforts are notable as they exist in the context of regional geographies and their directions, a circumstance well in line with PRC interests to expand influence through regionally-tailored approaches. These approaches fit well within the Lusophone “region’s” penchant for multilateralism, as is best seen through the Comunidade dos Paises de Lingua Portuguesa (CPLP). This trend exists in parallel with the reality that the CPLP as a whole – and especially in Africa – has little digital economy policy history that includes robust AI regulation. [11] That said, large multinational technology corporations like Microsoft have been involved in explorations of AI-driven healthcare solutions in select member states. [12] [13] Healthcare is a critical industry that can be enhanced through proper AI deployment, which Beijing appears to understand well within the context of relations with CPLP countries. Macau plays an important role here as a hub for Chinese health diplomacy. The MF Health Initiatives program has experience supporting foreign and developing societies with healthcare cooperation efforts in complex cases ranging from COVID-19 response to effective health technology production in pharmaceuticals to hospital equipment and public health outreach delivery. [14]

Africa

The Lusophone African countries base their AI policy directions on a plan drafted by the African Union (AU) in July 2024. This “Continental AI Strategy” is intended to promote ethical and equitable AI use across the continent. The plan includes a focus on encouraging job creation, economic development, and regional integration as can be assisted through improving AI. The plan also derives much of its power from a desire for policy implementation unity where AU members can harmonize strategies to gain more influence on future global AI conversations. [15]

The multilateral organization of Portuguese-speaking African countries known as PALOP (Paises Africanos com Lingua Oficial Portugesa) plays a role in many Lusophone states’ encounters with AI. PRC activities in the PALOP have been more limited in developing access to advanced technologies for aid recipients. PRC investment recently focused on large-scale industrial technologies designed to benefit the domestic Chinese economy through infrastructure, energy, and rudimentary digital connectivity projects. This runs counter to PALOP interest in improving AI for agriculture, logistics, and smart energy management/conservation [16]. This reality is reflective of broader trends in Africa as a whole, and especially in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), where several Lusophone countries also belong [17].

Brazil

Brazil takes an impactful stance in this area, as it is above average in its region in mature AI development, implementation, infrastructure, regulation, and research. Brazil has centralized the maximization of AI through a framework connecting policies and institutions to sustainable ICT objectives which build upon a talent base that is less likely to result in “brain drain” (unlike many of Brazil’s neighbors). Brazil has further developed its economy by leveraging known and powerful AI tools through institutions like the Brazilian AI Observatory that use Amazon Web Services (AWS) to support technical education. [18] Brazil’s emphasis on improving its ability to use ICT sustainably is key background for its positions towards AI. This first became a public concern for Brasilia in 2018 as it changed its outlook from defensively protecting its domestic internet through insular digital governance to a more outward approach. Brazil engaged in new trade agreements that targeted more favorable outcomes in digital commerce in cases ranging from the Brazil-Chile Free Trade Agreement and the Mercosur E-commerce Agreement. As a result, Brazil is an outstanding voice in promoting liberalized digital trade with an emphasis on consumer protection and data privacy. [19]

These conclusions result in a greater need for legal and law enforcement standards and regulations that can keep up with the challenges and priorities established by the Brazilian government. The general framework is not surprisingly carried out through judicial structures. Brasilia appears keen to adopt workable AI legal practices by leveraging academia and the startup community, particularly in the development of AI tools to aid the unique demands of legal professionals to effectively and sustainably streamline judicial systems. As such, China’s vast implementation of AI in its legal/law enforcement environment may be a model to watch for interested states like Brazil. [20]

European Union (Portugal)

Europe is a leader in AI regulation, which has global consequences for large governments like the PRC. The potential for conflict between this bloc of Western states (which includes Portugal) and Beijing becomes clearer by the day given that PRC-backed investment and innovation easily overlooks the EU’s priority of ethical AI use/development, data protection, and robust mechanisms for oversight. The two sides further diverge given China’s bent towards industrial policy and military-civil fusion over European concerns for human-centric use, sociolegal transparency, and risk management. For Europe, China’s AI prowess and innovation present economic opportunities in trade and potential cooperation alongside a challenge to protect the public from macroeconomic and individual harm. [21]

Conclusion

This analysis presents just one case study into how China’s investment and development of advanced artificial intelligence should give international observers pause as to how relations in a tech-dominated world will be pursued by individual state actors. The case of the Lusophone countries shows that there is now the potential for a new historical reality for countries (especially post-colonial ones) that may run counter to traditional Western thinking. In this way, AI advancements as influenced at least in part by China will underline how states like the Lusophone countries will continue to lead the “Global South” [22] toward a path that may not always completely align with great power interests. For its part, China is in position to continue strong international relations with the Portuguese-speaking states through its historical tie to the former Portuguese colony of Macau, and such appeals to history could determine future advancements and adoption of AI for the purposes of the Lusophone states. [23]

For the time being, however, the Portuguese-speaking countries are bound by a series of potential inflection points where they must decide new direction in an AI-driven world. For Portugal, this entails balancing its bilateral connections with China and other diplomatic entities with its European identity and commitments. For Brazil, AI may represent a chance for Brasilia to assert itself as a power of the developing world/”Global South” while underscoring the dynamics of its modern-day relationship with Beijing. Finally, Lusophone African countries are of particular interest for policy analyst observation in the short to medium term, as patterns of development aid and access to economic growth may be shifting in the AI age.

References

- William J. Vogt, “Non-Western Powers Reaching Singularity: Examining a Potential Future Outcome of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Development in the Case Study of China”, SSRN (July 22, 2025), available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5361860

- William J. Vogt, “Artificial Intelligence ‘With Chinese Characteristics’: A New Model for a New Age”, SSRN (July 06, 2025), available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5341204

- Amanda Holpuch, “'A Fight for Our Lives': Trump's USAID Freeze Is Harming Millions of People”, The Guardian, 13 Feb. 2025, available at: www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/13/usaid-funding-freeze-health

- African Union, “Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy: Harnessing AI for Africa’s Development and Prosperity”, July 2024, available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/44004-doc-EN-_Continental_AI_Strategy_July_2024.pdf

- Tatoli (Agencia Noticiosa de Timor-Leste), “AI representative pledges to support TL with innovative technology.”, 27 May 2024, available at: https://en.tatoli.tl/2024/05/27/ai-representative-pledges-to-support-tl-with-innovative-technology-2/17/

- Si Ying Thian, “#DigiGovSpotlight ‘60% of vital public services to go online by 2026’ – Cabo Verde’s digital government Chief.”, GovInsider Asia, 25 March 2024, available at: https://govinsider.asia/intl-en/article/60percent-of-vital-public-services-to-go-online-by-2026-cabo-verdes-digital-government-chief

- United Nations University, “National Strategy for Digital Transformation in Guinea Bissau.”, 11 July 2024, available at: https://unu.edu/egov/project/national-strategy-digital-transformation-guinea-bissau

- United Nations University, “National Strategy for Digital Transformation in Sao Tome and Principe.”, 5 January 2020, available at: https://unu.edu/egov/project/national-strategy-digital-governance-sao-tome-and-principe

- OECD, “National AI Policies and Strategies.”, available at: https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards/overview

- Amanda Holpuch, “'A Fight for Our Lives': Trump's USAID Freeze Is Harming Millions of People”, The Guardian, 13 Feb. 2025, available at: www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/13/usaid-funding-freeze-health

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “Africa Technology Policy Tracker.”, 2024, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/features/africa-digital-regulations

- Hayley Johnson, "Unlocking the Future: How Portuguese-Speaking Nations Are Harnessing AI for Inclusion.", DSA, 31 Jan. 2025, available at: https://dsa.si/news/unlocking-the-future-how-portuguese-speaking-nations-are-harnessing-ai-for-inclusion/14575/

- Sean O'Connor, "How Chinese Companies Facilitate Technology Transfer from the United States.", U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 6 May 2019, available at: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/How%20Chinese%20Companies%20Facilitate%20Tech%20Transfer%20from%20the%20US.pdf

- Marcus Verly-Miguel, "Participação do Secretariado Permanente do Fórum de Macau em iniciativas de Saúde Global entre 2015 e 2022.", Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva 34 (2024): e34047, available at: https://www.scielo.br/j/physis/a/Rd4jgJKqyqX7QyDtLJYv5cL/

- African Union, “Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy: Harnessing AI for Africa’s Development and Prosperity”, July 2024, available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/44004-doc-EN-_Continental_AI_Strategy_July_2024.pdf

- Fernanda Ilhéu and Joana Campos, "Cooperação Portugal–China na industrialização dos PALOP, no âmbito da BRI.", Rotas a Oriente. Revista de estudos sino-portugueses 1 (2021): 67-88.

- Klemens Katterbauer et al., "The Impact of AI on ECOWAS Energy Regulation Development.", Journal of Recycling Economy & Sustainability Policy 2, no. 2 (2023): 45-56, available at: https://respjournal.com/index.php/pub/article/view/41/29

- Centro Nacional de Inteligencia Artificial (Chile), “Indice Latinoamericano de Inteligencia Artificial.”, 2024, available at: https://indicelatam.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ILIA_2024_2.pdf

- Lucas da Silva Tasquetto et al., "O Brasil em meio à corrida regulatória pela governança da economia digital.", Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas 13, no. 3 (2023), available at: https://www.academia.edu/86039664/O_BRASIL_EM_MEIO_%C3%80_CORRIDA_REGULAT%C3%93RIA_PELA_GOVERNAN%C3%87A_DA_ECONOMIA_DIGITAL

- Guilherme Leão Melo, "Inteligência artificial e prestação jurisdicional: da China ao Brasil.", Revista de Direito 16, no.1 (2024): 01-29, available at: https://periodicos.ufv.br/revistadir/article/view/18484

- Celio Hiratuka and Antonio Carlos Diegues, “Inteligência artificial na estratégia de desenvolvimento da China con temporânea.”, Instituto de Economia, UNICAMP, 2021, available at: https://www.economia.unicamp.br/images/arquivos/artigos/TD/TD422_1.pdf

- Penqin Chen and Meng Jingwen, “Research on the Rise of the ‘Global South’ and International Development Cooperation between China and Portuguese Speaking Countries.”, Dongfang Journal 3 (2024), available at: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2024&filename=DFXK202403005&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=QQkQqsaoKP42iNbjwceen0XOZ0slVYaxihJchtk5aQlR0h45GFU91Ux7-4yoDhBR

- Vogt, "China and Lusophonia".

This article is part of the project Chinese Technological Investment in PortugueseSpeaking Countries. Learn more about this and other projects here.

The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the institutional position of Observa China 观中国 and are the sole responsibility of the author.

OBSERVA CHINA 观中国 BULLETIN

Subscribe to the bi-weekly newsletter to know everything about those who think and analyze today's China.

© 2026 Observa China 观中国. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy & Terms and Conditions of Use.