Sino-Lusophone Relations in the Information Age

A Key Diplomatic Case Study

versão portuguesa disponível

First article of this project Research for this project was supported by the Graduate Startup Interns Program and the Virtual Immersions and Experiential Work Program (both at Georgetown University).

Introduction

China’s influence in modern international affairs cannot be understated. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has emerged as a competing world power with a clear intention to expand its hard and soft power to new places and markets. This importantly includes smaller and emerging market countries where great power attention may have been lacking. Here, pitches to foreign nations to obtain greater collaboration and support for Beijing have cultural overtones, as these states’ perceptions of China are formed by historical experience and prior connection to trade networks that spread values along with products and new economic structures.

One overlooked but highly relevant case study to consider in Chinese foreign relations today is in its activities and diplomacy in the Portuguese-speaking countries (Portugal, Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Timor-Leste/East Timor, Guinea-Bissau, Cabo/Cape Verde, Sao Tome and Principe). These states formed a wide ranging, global empire that directly interacted with China through the Portuguese control of Asia territories, namely the current PRC holding of Macau. From such a connection it is evident that Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) areas have a direct cultural connection to China which may support a natural default affinity with Beijing. [1]

In this way, Beijing is in a strong position to increase its influence in Lusophone states and has a vested interest in taking advantage of such a situation. The impacts of this reality are magnified by the role of information communication technologies (ICTs) and the investment potential China has in supporting Lusophone market development in this area. This article thus explores the dynamics between China and the Portuguese-speaking states that would exist in the all-important technology sector and suggests a potential for solidification for strong continuing relations between China and these countries.

Chinese Foreign Policy Trends

China’s default approach to foreign policy is well captured by Jose Carlos Matias, who describes it as “pragmatic” and not “ideological”. [2] As scholars like Lucy Corkin also note, Lusophone Africa in particular “is seen as a testing ground” for trade and diplomatic agendas. [3] This is evident as China seeks to grow its “state capitalist” model where national governments control industry and economic production expanding its global reach while spreading its socioeconomic values to new places. [4] Given that ICT constitutes one of the largest economic, business, and utility sectors in the world, these realities are especially pertinent in contemporary international development analysis.

China benefits from its current control over the Macau Special Administrative Region (SAR), a Portuguese-speaking possession. The SAR’s special identity within the PRC political system is evident through its unique governance structure based on Portuguese civil law. Although the territory is known for is gaming and tourism sectors, both Beijing and Macau see the SAR as an appropriate area for economic diversification through critical industries such as financial services, information technology, and global commerce. In the latter sector, the SAR actively promotes trade relationships in Portuguese-speaking markets with the hope of capitalizing on cultural similarities. [5]

This approach extends specifically through the Macau Forum (MF), which is designed to foster trade and collaboration between China and Lusophonia by leveraging Macau’s unique history and identity as a Chinese and Portuguese-speaking society. [6] The MF focuses on key areas like energy, infrastructure, and agriculture, all of which are empowered by ICT. However, its reach may be limited as Lusophone actors like Brazil balk at China’s dominant voice as seen in Beijing’s insistence on a skewed Taiwan dialogue within the MF. [7] Here, the “Beijing Consensus” emerges given China’s attempt at “Global South” cooperation that on the surface more fairly distributes development aid, emphasizing the mutual benefits involved between donors and recipients. [8] For the PRC, this spirit of cooperation is meant to ensure new market access for critical natural resources and lucrative consumer bases. [9]

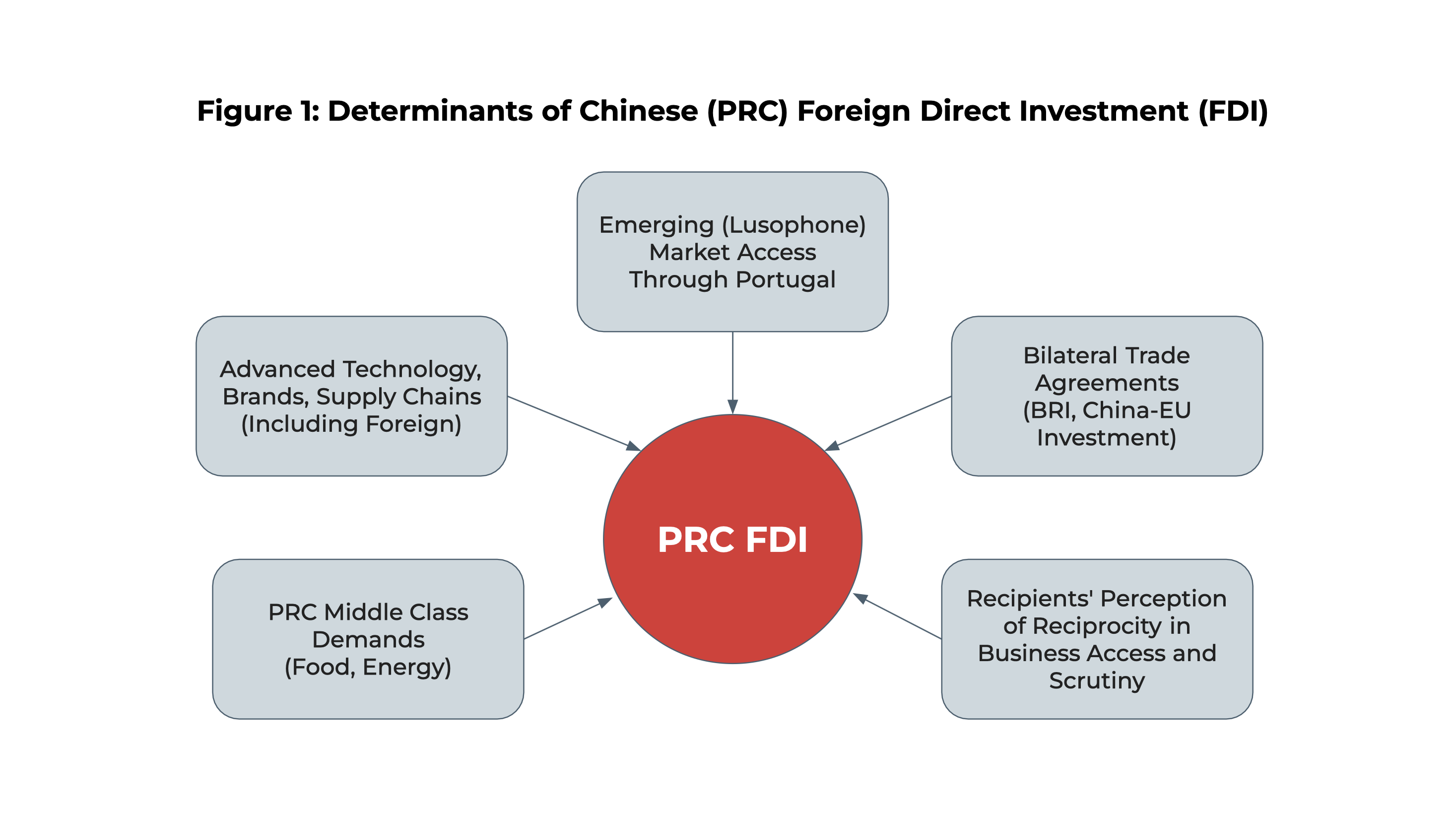

In this conversation Africa stands out as a region that may be inclined towards ideological conversion to the recognized “China model”. From Beijing’s viewpoint, Africa is a laboratory for outsiders to experiment with new political and trade mechanisms while providing China with critical resources, including extraction opportunities, worthwhile export destinations, growing geopolitical legitimacy, and trade security. [10] This PRC economic growth emphasis also focuses heavily on infrastructure projects through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Digital Silk Road (DSR), encouraging stimulus to drive Chinese employment and output. [11] This is illustrated further in Figure 1 below

Vogt (2017) previously observed that China is uniquely positioned to take advantage of the overall Lusophone diplomatic position as it considers its international development strategy; this extends to high-impact industries like ICT. In the current era, China’s investment portfolio is informed by a broad historical awareness of international development loan programs. [12] The resulting financial picture adds weight and controversy to China’s affairs in Lusophone states given that terms of credit can include elements giving China more control – and even partial sovereignty – over critical industries, ports, and the hiring for major projects (often in the form of imported Chinese labor). [13]

China’s Goals in Africa

The African continent boasts the largest array of Lusophone states and is thus a key region to consider. China has long engaged with the African continent and has a record of trade engagement. [14] Among other drivers, Africa’s geography lies in a geopolitically strategic location between the Middle East and Europe and includes natural resources in many of its countries – though not as much in Cabo Verde (CV). [15] Importantly, Africa has some of the world’s most fertile fishing waters which can feed a wealthier Chinese population more inclined to eat higher value sustenance (like seafood). [16] This is especially evident in Guinea-Bissau’s (GB) plentiful territorial waters where fishing rights are coveted by foreign powers like the PRC. [17]

Lusophone Africa’s lengthy relationship with China is therefore defined by an affinity toward Maoism and a closeness due to two primary factors: [18]

- The CCP extended contact to African countries early in its reign (post-1949);

- African countries sought Marxism to drive their independence movements and later fuel civil wars. Marxism was particularly attractive because it directly countered the fascism espoused by the ruling (and waning) Portuguese colonial powers led at the time by a right-wing dictatorship.

China similarly continues its involvement in Lusophone Africa through several institutional mechanisms. The most important of these is the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC or 中非合作论坛 zhongfei hezuo luntan), which has more recently engaged in Lusophone artificial intelligence-related cooperation. Through FOCAC, China signals its intentions towards the continent. in the foreseeable future. This makes Chinese actions in Lusophone Africa a useful arbiter of Beijing’s path forward in its foreign policy overall.

On the other hand, a point of current tension between China and African states is the overall racist attitude of Chinese society towards Africans in China. African nationals were subjected to widespread forced coronavirus testing (as a targeted population assumed to be more likely to carry the virus) and extended lockdown measures – including forced evictions – which threatened the lives and livelihoods of African immigrants. [19] The strain and anger evident in African accusations of Chinese racism intensified other tensions, namely the heavy debt obligations placed on African nations from BRI. [20] This especially harms West African nations like Cabo Verde that have high government debt and few natural resources for adequate repayment. [21]

Pan-Lusophone Interests

In occupying this unique geopolitical space, Lusophonia is defined by a shared Portuguese colonial heritage pointed towards global trade, Westphalian sovereignty from distinct national borders, and a series of independence movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. China has a mature relationship with Lisbon due to Portugal’s colonial presence in a previous global trading empire. [22] This is most clearly seen in the case of Macau, a Portuguese territory on Chinese soil until 1999. The Sino-Portuguese connection there still resonates and extends to other parts of the former Portuguese empire. [23]

Lusophone countries recognize their shared heritage and similar sociopolitical makeups by creating meaningful institutions to collaborate, spread ideas, and coordinate policy advocacy. These multilateral communities represent a large diaspora, with inhabitants linking Europe, Africa, and South America and include:

- Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa (CPLP, or the Community of Portuguese-speaking Countries);

- Países Africanos de Lingual Oficial Portuguesa (PALOP, or the Portuguese-speaking African Countries);

- Partido Africano para a Independência da Guine e Cabo Verde (PAIGC, or the African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde).

- BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa)

PRC global emergence increased the power of non-Western multilateral diplomacy via organizations like BRICS. Brazil, the largest Lusophone state, is leading the charge to open up BRICS membership for “geographic equilibrium,” further supporting Beijing’s objectives and the position of stridently authoritarian Western antagonists like the PRC and Russia. [24] That said, Brazilian diplomacy in this area puts Brasilia in a difficult position because it raises the cost of doing business with China due to countervailing pressures from the US and partners like Portugal who must consider major democratic alliance commitments.

As a leading voice amongst non-aligned states, Brazil’s trade relations are also a noteworthy indicator of whether a pan-Lusophone stance facing non-Western cultures like China is present and sustainable. The wave of protectionism spreading across the world thus presents a thorny question for Brasilia. The response of strong Brazilian protectionism embodies a national unity towards PRC trade and overcapacity/dumping, as seen when Brazil levied tariffs on the PRC in ICT product manufacturing. However, Beijing is not showing a willingness to retaliate in the short term, which could signal that there remain other aspects of bilateral affairs that are much more important for Beijing to secure support from Brazil in its “Global South” dealings.

Concluding Thoughts

The PRC appears well-positioned to continue its relationships with the Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) states in the foreseeable future. This reality is built on a multi-pronged foundation as explored in this article. This foundation represents a basis for a core diplomatic strategy for Beijing in critical areas such as the emerging markets of the “Global South.”

One aspect of this foundation that stands out is the use of institutional mechanisms to solidify relations between China and these states. This aligns well with the interests of Lusophone states themselves who have created their own multilateral organizations to promote development, security, and other aspects key to national and international prosperity. These organizations additionally highlight how the Lusophone countries interact closely with one another and for this reason can be viewed as a “regional” bloc even though the individual states lie far apart from each other geographically.

This closeness as defined by shared history and cultural background exists in tandem with other fusions of common culture in interactions with the PRC. Here, the emphasis on Africa as a key part of international development efforts – especially in critical sectors like information technology and artificial intelligence – is a major target for foreign direct investment efforts from large world powers at a time when development financing is changing. Chinese activities in this area could thus create a new “Global South” that develops according to non-Western economic models, a significant development in international affairs.

As a result, China and the Portuguese-speaking countries have a series of intertwined relationships that are worth watching and analyzing in any consumption of current affairs today. Such diplomacy is making a substantial impact on the dynamics of international relations as China continues its rise as a globally relevant power. Consequently, the case study of its interactions with Lusohphone states give highly relevant clues as to the direction of Beijing’s foreign policy in the short to medium term and should be studied further.

References

- William J. Vogt, “China and Lusophonia: A Compatible Alliance Network?” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 3, no. 4 (2017): 551–73.

- Jose Carlos Matias, “Macau, China and the Portuguese Speaking Countries,” working paper presented at Inside/Outside: 60 Years of Chinese Politics – Hong Kong Political Science Association 2009 Conference, August 20–21, 2009, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

- Lucy J. Corkin, “China’s Rising Soft Power: The Role of Rhetoric in Constructing China-Africa Relations.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 57, no. SPE (2014): 49–72.

- Andrew Szamosszegi and Cole Kyle, An Analysis of State-Owned Enterprises and State Capitalism in China, vol. 52 (Washington, DC: Capital Trade, Incorporated for US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2011); Julan Du and Yifei Zhang, “Does One Belt One Road Initiative Promote Chinese Overseas Direct Investment?” China Economic Review 47 (2018): 189–205.

- Olívia Pestana and Vítor Gomes Teixeira, Roteiro para conhecer e negociar em Macau: informações relevantes para negociação numa cultura euro-asiática, in A negociação como processo infocomunicacional e intercultural: o que os negociadores precisam saber em países de língua portuguesa (Porto: Universidade do Porto; Lisboa: Universidade Católica Portuguesa, 2021).

- The Digital Silk Road (DSR) translates into simplified Chinese as 数字丝绸之路 shuzi sichou zhilu. Pestana and Teixeira, Roteiro para conhecer e negociar em Macau; Eden Liu de Castro, A relação entre as comunidades de Macau e a identidade das pessoas de Macau (master’s thesis, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 2022); Bi Meng Yin, “Os retornados chineses da América Latina em Macau,” Fragmentum, no. 35 (Oct./Dec. 2012): 1–15, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/270300058.pdf

- Carmen Amado Mendes, “A relevância do Fórum Macau: o Fórum para a Cooperação Econômica e Comercial entre a China e os Países de Língua Portuguesa,” Nação e Defesa, no. 134 (2013): 279–96.

- Pengqin Chen and Meng Jingwen, “Research on the Rise of the ‘Global South’ and International Development Cooperation between China and Portuguese Speaking Countries,” Dongfang Journal, no. 3 (2024).

- Carolina Maria Pereira Rodrigues Machado, O mundo lusófono na política de cooperação da China (master’s thesis, Universidade Lusófona, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais, Educação e Administração, Lisbon, 2023).

- Corkin, “China's Rising Soft Power”; Larry Hanauer and Lyle J. Morris, Chinese Engagement in Africa: Drivers, Reactions, and Implications for US Policy (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2014).

- Carlos David Gaspar Loureiro, As relações económicas luso-chinesas (master’s thesis, Universidade do Porto, 2015); Jorge Malena, “The Extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and Potential Risks, the DSR’s Origins and Its Initial Development,” ResearchGate, January 2021; AidData (College of William and Mary), How China Lends: A Rare Look into China’s Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments (Williamsburg, VA: AidData, November 15, 2022), available at https://www.aiddata.org/publications/how-china-lends-journal-article

- AidData, How China Lends.

- Brahma Chellaney, “China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, January 24, 2017, available at https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy/

- Vogt, “China and Lusophonia.”

- Leandro do Rosário Viana Duarte, Kedong Yin, and Xuemei Li, “The Relationship between FDI, Economic Growth and Financial Development in Cabo Verde,” International Journal of Economics and Finance 9, no. 5 (2017): 132–42.

- Panos Mourdoukoutas, “What China Wants from Africa? Everything,” Forbes, May 4, 2019.

- Peter Karibe Mendy and Richard A. Lobban Jr., Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2013); Michael E. Clark, “A More Comprehensive Plan to Push Back Against China’s Fishing Practices,” War on the Rocks, April 25, 2024, available at https://warontherocks.com/2024/04/a-more-comprehensive-plan-to-push-back-against-chinas-fishing-practices/

- Vogt, “China and Lusophonia.”

- Simon Marks, “Coronavirus Ends China’s Honeymoon in Africa,” Politico, April 16, 2020; Duarte, Yin, and Li, “The Relationship between FDI”; Danny Vincent, “Africans in China: We Face Coronavirus Discrimination,” BBC News, April 17, 2020; Bonnie Girard, “Racism Is Alive and Well in China,” The Diplomat, April 23, 2020.

- Marks, “Coronavirus Ends China’s Honeymoon in Africa.”

- Duarte, Yin, and Li, “The Relationship between FDI.”

- Oxford Reference, “Westphalian State System,” available at https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803121924198

- Vogt, “China and Lusophonia.”

- African Union, Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy (Addis Ababa: African Union, July 2024), available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/44004-doc-EN-_Continental_AI_Strategy_July_2024.pdf

This article is part of the project Chinese Technological Investment in PortugueseSpeaking Countries. Learn more about this and other projects here.

The opinions expressed in this article do not reflect the institutional position of Observa China 观中国 and are the sole responsibility of the author.

OBSERVA CHINA 观中国 BULLETIN

Subscribe to the bi-weekly newsletter to know everything about those who think and analyze today's China.

© 2026 Observa China 观中国. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy & Terms and Conditions of Use.